This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Conducting a Yogic Assessment

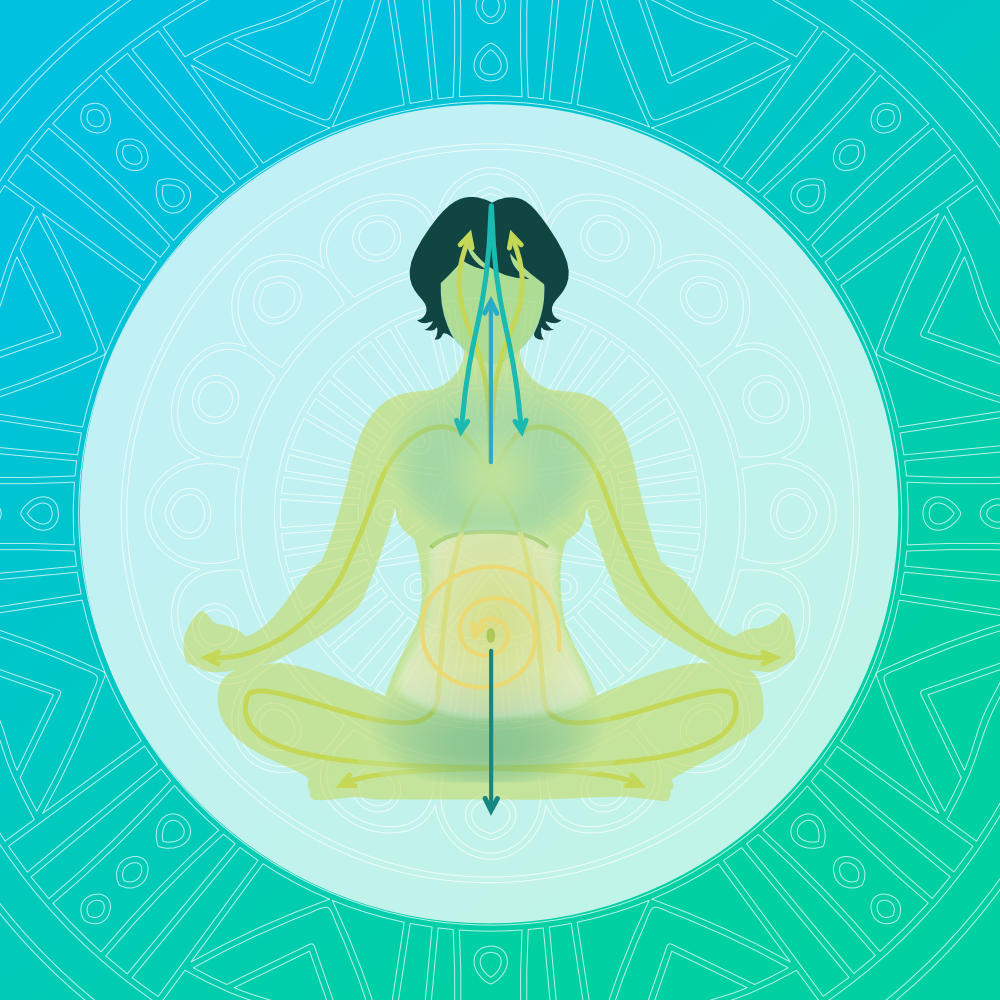

When a doctor (or a patient) is zoomed in on a specific problem within a specific organ system, it can be hard to see the big picture of how it fits within the context of the entire organism. In yoga therapy, we usually adopt the “zoom out” approach and try to see how a specific health issue fits with the students’ overall constitutional, energetic, and psychological state. That is why, instead of zooming in on a particular organ, in yoga therapy we step back and take a bird’s eye view of the student’s constitution (the Ayurvedic model), the movement of nourishment throughout the system (the Pancha Vayu model), and the states of excess and deficiency within each of the body’s main energetic centers (the Chakra model). These models are invaluable for assessing the student’s system-wide state of health and well-being and for choosing specific strategies we can employ to facilitate healing.

Generally speaking, a model is a simplified representation of some realities that exist in the physical world; it is a mental construct put together to promote better understanding of the world around us and our internal state. Each model usually has its own main concepts that are organized in a particular way and are used to understand certain parts of the reality. In yoga therapy, the reality that we are trying to understand is the totality of the human body, including its physical structure, physiology, psychology, and spirituality. We are also trying to explain how the six major factors—diet, environment, lifestyle, movement, breathing, and mental activities—can be used to restore balance and promote health and well-being.

The Panchamaya Model

Over the centuries, the yoga tradition has accumulated a vast body of knowledge on ways to relieve human suffering and promote better health and well-being. The Panchamaya model (or Five Koshas model), described in The Taittiriya Upanishad, is a way to organize our thinking when it comes to the five main layers of our systems: physical structure; physiological processes; the content of our minds; ideas and attitudes toward our surroundings; and our sense of connection to other people, society, culture, and the Universe. The yoga tradition has developed a variety of methods to bring balance and healing to each of these layers with a specific set of tools.

When yoga teachers and therapists assess their students and chart the course for their work together, they must take into account all aspects of each student’s mind, body, and spirit as well as the student’s family situation, work environment, socioeconomic status, and cultural context. They must also consider each student’s habits, routines, values, beliefs, and rituals.

The Panchamaya Model serves as a foundation of all work with yoga students. Yoga teachers and yoga therapists choose from a variety of yogic tools that address different layers of the student’s system.

The Ayurvedic Model

The Ayurvedic model uses the concepts of qualities (dryness, lightness, heat, density, etc.) and their associated functions (mobility, metabolic activity, stability, etc.) to maintain and restore the individual’s health. According to the Ayurvedic model, those qualities and functions are represented within everyone in certain quantities and are part of our constitutional makeup. However, if those qualities become significantly increased or decreased, it creates an imbalance and leads to health issues. Knowing your constitutional predispositions toward specific imbalances helps you avoid things that might aggravate the imbalance and correct the imbalance once it manifests.

How to conduct an Ayurvedic Assessment

- Identify the student’s dominant dosha(s) through observation and conversation. Observe your student’s physical characteristics, ask questions about their physiological processes, and note their demeanor.

- Identify your student’s balanced characteristics. Answer the question, “How do I know that the student is vata (pitta/kapha) dominant?” For example, you might deduce that your student is kapha dominant if they have a large frame, thick hair, smooth skin, and appear to be slow, measured, and thoughtful in their temperament.

- Note the main qualities of the specific Ayurvedic type that you’ve noticed in your student.Sometimes the dominant quality is obvious, and sometimes it isn’t. For example, your student might exhibit multiple signs of disorganized movement (the quality of mobility), they might have a very intense, penetrating gaze as well as a keen and engaged mind (the quality of sharpness), or they might have slow speech, methodical movements, and a mellow demeanor (the quality of slowness). The longer you practice, the easier it will be to identify the most prominent qualities.

- Identify the signs and locations of imbalance. Analyze the symptoms of discomfort that your student communicates and note whether they indicate an imbalance in a particular dosha and whether they have a particular quality in common. For example, your student might be complaining of joint pain while also having dry skin, rigid movements, and stiff, cracking joints. This might indicate a vata imbalance with the quality of dryness.

- Summarize your observations about the student’s current state. After recording your notes about your student’s constitution, pronounced qualities, and type of symptoms, it helps to summarize your thoughts and formulate a vision of what you think is going on from the Ayurvedic perspective.

- List your practice recommendations. Based on your summary, you can devise a course of action and outline the strategies to implement into your work with your student. If the system-wide imbalance is prominent, this can become your primary area of focus; if it’s minor, you can use your knowledge of the student’s constitution to better tailor your practice to their temperament and personality.

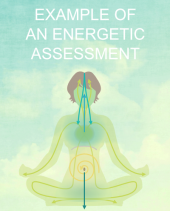

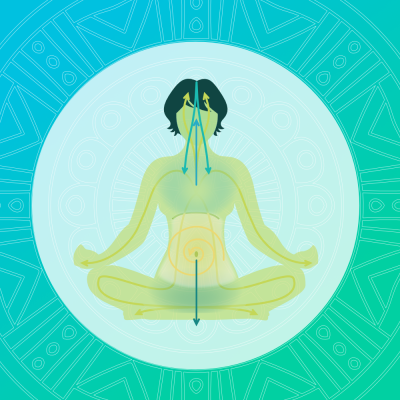

The Pancha Vayu Model

As part of a therapeutic assessment, we evaluate the movement of vital energy (prana) throughout the system. Prana is said to be the force that animates all living things. Prana is a manifestation of all energy. As humans, we replenish our prana through food, water, air, and experiences. Once we learn how to understand and guide our own prana, there will be no limits to our powers. Breath is a vehicle of prana. The science of pranayama is a fundamental part of the yoga practice because its goal is to expand and harness our life force energy. In yoga therapy, when a student describes a specific health challenge, we try to understand it from the perspective of a subtle energetic imbalance. We can use the traditional Panchavayu model to understand the directions of the strongest energy movement and the impeded energy flow.

How to conduct an Energetic Assessment

The Pancha Vayu model is most useful when the student experiences physiological challenges, although the vayu imbalance also shows up on the physical and mental–emotional levels. This is a subtle system, and sometimes there are no clear patterns of imbalance. Below are some steps you can take to see whether this model would be applicable to your student’s challenges.

- Identify the student’s primary locations of discomfort and unease through observation and conversation. Observe your students’ body language, ask about the symptoms they experience, and discuss their daily activities and lifestyle. Note if there are specific areas of the body that seem particularly painful, sensitive, contracted, or guarded. If there are, identify which vayu resides in that location.

- Note the directions of the strongest and of the impeded energy movement. Take a bird’s eye view of the student’s current challenges and patterns of behavior to identify which direction(s) of subtle energy movement seem the most pronounced (taking stuff in, processing it, distributing it, eliminating it, or getting nourishment from it) and which one(s) the student is having trouble with. For example, a new mother might have trouble taking things in (which manifests as gasping inhalation, restricted ribcage expansion, skipped meals, anxiety, and an inability to ask for help). She might also exhibit a very strong giving/eliminating pattern (which shows up as a lack of energy due to resource depletion, frequent urination, incontinence, and obsessive focus on the needs of her infant at the expense of her own). This would point to an imbalance in both prana and apana vayus.

- Identify which physiological systems seem to be affected. Methodically go through all the major physiological systems and note whether the identified pattern is manifesting anywhere else. Mark the system(s) where the pattern appears to be present and describe its manifestation. For example, the pattern of the new mother mentioned above could also show up in the following systems: sensory (as a limited ability to take in new information), nervous (as being forgetful), digestive (as diarrhea), muscular (as pelvic floor weakness), and lymphatic (as swelling of the feet and ankles).

- Summarize your observations about the student’s current state. After recording your notes about the locations of your student’s imbalance, the direction(s) of the strongest and impeded energy movement, and the physiological systems affected, record your thoughts, and formulate a vision of what you think is going on from the pancha vayu perspective.

- List your practice recommendations. Based on your summary, devise a course of action, and outline the strategies to include in your work with your student. Ask yourself, “How can the energy flow be restored/redirected to relieve the areas of congestion or insufficient concentration?” Be sure to use breath as a vehicle of prana, asana as prana pumps, pranayama as an energy regulating device, and attention as an energy redirection tool.

The Chakra Model

For ancient yogis, chakras were potent energy centers along the main energetic channel of the body (sushumna nadi). This is where the secondary energetic channels (ida and pingala) are said to cross. The intersection of all three major channels creates energy concentrations that affect our functioning. When the energy is flowing freely, the chakra wheels are said to be spinning smoothly, much like water wheels under the smooth flow of water. When the energy becomes clogged, the chakras’ functioning is affected, and all sorts of problems sprout up in the affected area.

You can think of chakras as clusters of beliefs around specific needs that we all have (e.g., safety, procreation, achievement, love, self-expression, meaning, and inspiration). Each of us has a wide variety of beliefs about these needs, affecting our perceptions and actions. When these beliefs get us what we need, they are effective, but if we keep struggling with the same issue over and over, then something in that cluster of beliefs is sabotaging our best efforts. And if we want to get these needs met, we need to re-evaluate these beliefs.

Chakra work allows us to do that, serving as a map to help us figure out where we are on the spectrum between function and dysfunction on the level of each need. Chakra work is meant to anchor our attention in a specific body area and use it as a focusing device to work out the issues that we are dealing with on each chakra’s level. We can use symbols associated with each chakra to unearth our beliefs and potentially change them.

How to conduct a Personality Assessment

The personality is formed based on inherent tendencies and is affected by our experience and conditioning. It has great potential for transformation. The Chakra model can serve as a map of personality.

Not every student will be open to an intentional dive into their deepest beliefs and analysis of the innermost layers of their personality. Before you begin this kind of work, be sure that your student is interested and open to that exploration. You don’t have to use chakra terminology to have important conversations with your students about their views of the world and their ways of interacting with it. If the student is not willing to do this kind of inner processing, you can use your own assessment of their personality to better tailor your yoga practice to their needs.

- Assess where the student stands on the level of each chakra through conversation and observation. This will serve as a jumping-off point. You can approach this investigation systematically, from the ground up, exploring each chakra and the beliefs your student has associated with it, or you can focus on the one that keeps coming up. For example, if the student keeps circling back to their fears, insecurities, and feelings of instability, you might decide to zoom in on muladhara (the root chakra).

- Get a sense of whether the beliefs around a specific chakra have a connection with the student’s current challenges. Analyze the symptoms of discomfort that your student communicates and note whether they seem to be connected to an imbalance in a particular chakra. For example, if the student complains of a frequent upset stomach and feelings of anxiety while also lacking self-confidence and willpower to handle the smallest challenges, it might point to an imbalance in Manipura (the navel chakra).

- Summarize your observations about the student’s current state. After recording your notes about your student’s chakra imbalances and obvious related symptoms, you can summarize your thoughts and formulate a vision of what you think is going on from the perspective of the Chakra model.

- List your practice recommendations. Based on your summary, you can devise a course of action and outline the strategies to implement into your work with your student. Rather than focusing on why the student has trouble with a particular chakra, it works better to encourage them to embody the balanced qualities of the chakra that they would like to cultivate. Symbolism works great for chakra work. Use relevant and meaningful imagery—elements, senses, animals, deities, and gestures— as focusing devices to cultivate the desired qualities. For example, you can use the image of a mountain to symbolize stability, the image of an eagle to enable your student to see the bigger picture, or the image of water to cultivate the feeling of fluidity.